Abstract

Last week, someone commented on my post about 47-day certificates:

users need to stop being stupid .. and revoke the certs … i mean you can go online and look at every cert issued … replace and revoke them .. that’s the users fault don’t force 45 day certs on the rest of us.

This perfectly captures our collective delusion that SSL certificate revocation works. You click a button, the certificate stops working.

And why wouldn’t we believe that? Every CA has a big “Revoke Certificate” button right there in the dashboard. It must do something, right?

Here’s the dirty truth: most revoked certificates keep working. We’ve known this for years, but we just keep the security theater going.

The revoked certificate that (mostly) still works

Let’s say you have a website called revoked.badssl.com. You suspect the private keys were compromised, so you want to revoke the certificate. Easy right? There’s a command line for that:

certbot revoke --cert-path /path/cert.pem

Success! It returns “Congratulations! You have successfully revoked the certificate”. Great! Go check it. Really, go load that URL. I’ll wait.

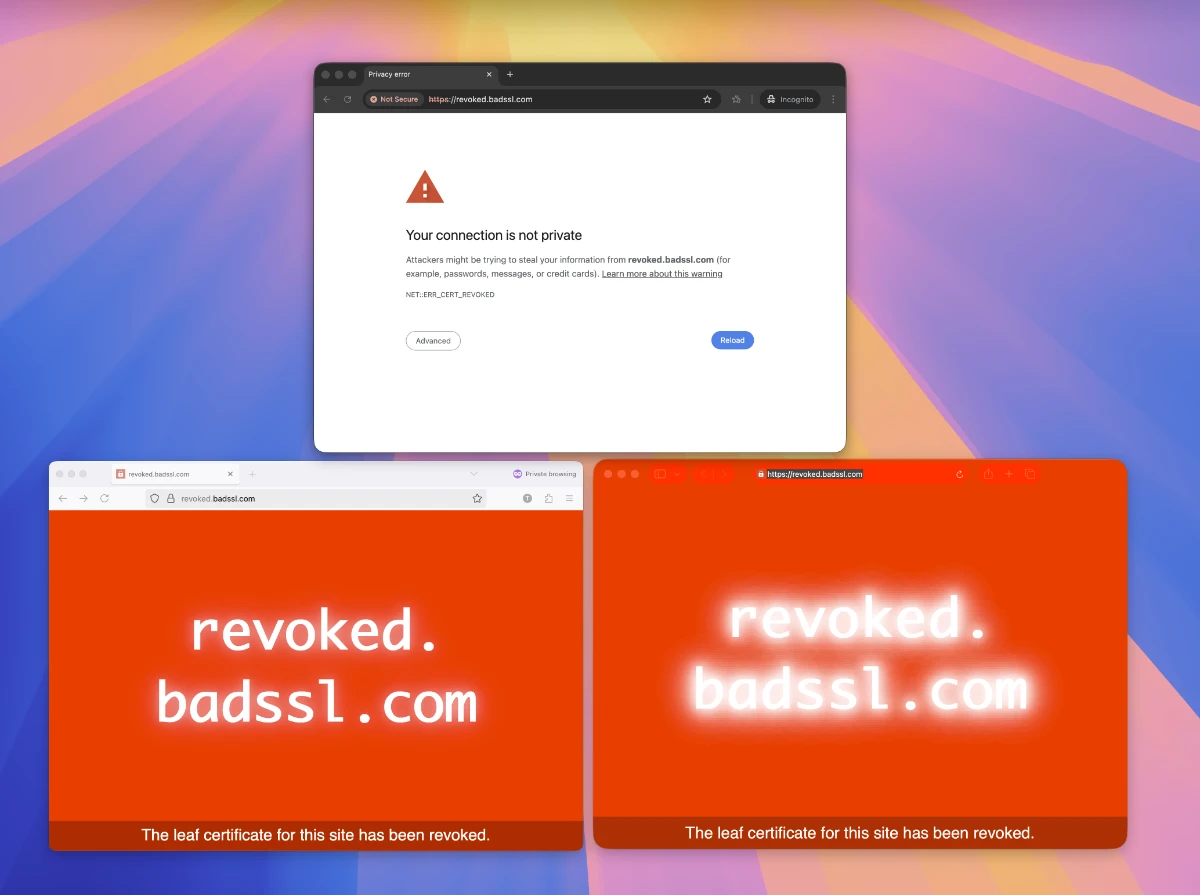

Depending on which browser you’re using, you’ll see different results. Chrome shows a scary “Your connection is not private” page, but Safari and Firefox loaded it just fine.

This isn’t because Safari and Firefox are broken or inferior. Every browser handles revocation differently. Chrome caught this one because someone at Google manually added this high-profile example to their CRLSet. Firefox and Safari might catch a different revoked certificate that Chrome misses.

Three browsers, three different revocation systems, three different results for the same revoked certificate.

This isn’t some obscure edge case. This is a certificate explicitly revoked for key compromise, the most serious reason possible. And whether it gets blocked depends entirely on which browser you happen to be using and whether that particular certificate made it into that browser’s proprietary revocation list.

A brief history of failing at revocation

CRLs: the small-scale solution

What is a certificate revocation list? Certificate Revocation Lists (CRLs) were simple. A X.509 standardized list of bad certificate serial numbers. When a certificate gets revoked, add it to the list. Browsers download the list and check if the certificate is on it. Easy.

This worked great when the internet only had hundreds of certificates.

But just a few years later, CRLs were already becoming unwieldy. Some CRLs grew to hundreds of megabytes. Imagine every browser downloading a 300MB file from every Certificate Authority, multiple times per day. On dial-up.

In addition to the size problem, CRLs were also constantly unavailable and hopelessly out of date as Certificate Authorities (CAs) struggled to scale their infrastructure with the exploding scope of the web.

OCSP: the cure is worse than the disease

In 1999, the IETF published RFC 2560 introducing OCSP (Online Certificate Status Protocol). Instead of downloading entire lists, browsers can query for specific certificates as needed. Real-time revocation checking.

Unfortunately, the CAs weren’t any better at keeping OCSP online than they were at CRLs. Mozilla’s reported that nearly half of their system failures were due to OCSP service outage or malformed OCSP responses. Google’s data showed median OCSP checks taking 300ms, with means approaching a second. Load a modern website with resources from 20 domains? That’s potential seconds of delay just for revocation checking.

OCSP was too slow and unreliable enough to count on for certificate checking. So what do we do when its offline?

-

Hard-fail: Block the connection. Sounds secure, except now every OCSP outage breaks the internet. One CA has an outage and millions of users can’t access sites.

-

Soft-fail: If OCSP doesn’t respond, allow the connection anyway. This is what browsers actually do.

That doesn’t sound so bad until you realize that the only time you really need OCSP is when you are being attacked, and the attacker can probably block OCSP requests if they are sending you an invalid certificate.

As Google’s Adam Langley said,

Soft-fail revocation checks are like a seat-belt that snaps when you crash. Even though it works 99% of the time, it’s worthless because it only works when you don’t need it.

As one final nail in the OCSP coffin, the architecture has a huge privacy problem. Every OCSP query tells the CA exactly which websites you’re visiting in real-time. Your browser checking the certificate for adultwebsite.com? The CA knows. Maybe the ISP too. Get ready for some uncomfortable targeted ads.

The industry tried to band-aid these problems with OCSP stapling. Let the webserver fetch its own OCSP response and include it with the certificate. No more privacy leaks. No more performance hit. No more soft-fail dilemma.

Clever solution, except it requires server operators to actually configure it. According to Netcraft’s SSL Survey, less than 5% of sites have OCSP stapling properly configured. Even when stapling is configured, it’s often broken. The stapled response expires, doesn’t get refreshed, and browsers fall back to soft-fail OCSP. We’re right back where we started.

Browsers gave up on OCSP and reinvented CRLs

The CRL vs OCSP debate is pointless when both proved fundamentally broken. Here’s where it gets absurd. After abandoning CRLs for being too big, then abandoning OCSP for being broken, browsers went back to… downloading lists of revoked certificates.

But instead of fixing the problem, they each built their own thing.

Chrome created CRLSets. As Adam Langley explained in the announcement, Chrome would crawl CRLs, compress them, and distribute updates through Chrome’s update mechanism. Except they only include “important” revocations.

How many is “important”? About 24,000 certificates. Meanwhile, crawling actual CRLs reveals over 2 million revoked certificates in the wild. That’s 98% of revoked certificates that Chrome simply ignores.

Google’s Adam Langley defended this saying CRLSets are “primarily a means by which Chrome can quickly block certificates in emergency situations.” Not comprehensive revocation checking. Just emergency response.

Firefox tried harder with CRLite, using Bloom filters to compress the full CRL dataset into about 10MB. Clever engineering, but the false positive rate means some valid certificates get flagged as revoked. The update lag means recently revoked certificates still work for days weeks.

Apple? They aggregate CRLs at the OS level. The details are fuzzy because Apple doesn’t document it, but your Mac is quietly downloading revocation lists in the background. The implementation is opaque and inconsistent.

Three major browsers, three different revocation approaches, three different sets of revoked certificates they’ll actually block. That certificate you revoked? Maybe it stops working in Chrome next week. Maybe Safari blocks it next month. Maybe Firefox never notices.

Everyone went back to CRL-style lists. Just proprietary, incompatible versions that work differently across browsers. A revoked certificate might be blocked in Chrome but work fine in Safari. Security theater at its finest.

The CA/Browser forum knows revocation is broken

The best part? Everyone knows this is broken. The CA/Browser Forum discussions are filled with admissions of defeat.

In a 2017 discussion, Ryan Sleevi from Google stated bluntly: “Revocation checking doesn’t work. It’s not a matter of opinion, it’s a matter of fact demonstrated through data.”

The Mozilla CA policies contain thread after thread of CAs reporting OCSP failures, arguing about CRL sizes, and generally acknowledging the whole system is held together with prayer and duct tape.

My favorite is from the discussion about shorter certificates: “Given that revocation is fundamentally broken and we have no realistic path to fixing it, shorter certificate lifetimes are our only option.”

There it is. The admission. We can’t figure out how to revoke certificates, so let’s just make them expire faster.

The industry’s “solution”: just give up

And that’s exactly what we’re doing. Can’t revoke certificates? Just make them expire before compromise becomes a problem.

The timeline tells the story:

- 2011: Certificates could be valid for 5+ years

- 2015: Maximum drops to 3 years

- 2018: Down to 2 years

- 2020: 398 days (just over 1 year)

- 2026: 200 days coming soon

- 2027: 100 days

- 2029: 47 days

The browsers pushed for 47-day certificates because they knew they couldn’t make certificate revocation work correctly. If we can’t revoke a compromised certificate, at least it’ll expire soon. 47 days of exposure is better than a year.

Except now everyone needs automated renewal. The same organizations that couldn’t configure OCSP stapling now need to rotate certificates every month and a half.

Living in a post-revocation world

So here we are. The entire SSL certificate revocation system is broken. Everyone knows it’s broken. The browsers gave up trying to fix it. The CAs keep the infrastructure running because compliance requires it. And we all pretend it works.

That “Revoke Certificate” button in your CA dashboard? It updates some lists that mostly nobody checks. Your revoked certificate goes into a CRL that’s too big to download, gets flagged in OCSP that browsers ignore, and maybe, eventually, possibly, gets added to Chrome’s CRLSet if Google feels like it.

The one silver lining? If you’ve got Perfect Forward Secrecy enabled, at least that compromised certificate can’t decrypt your historical traffic. Broken revocation means the attacker can still impersonate you, but they can’t read last year’s secrets. Small victories.

This is the broken system we’re protecting with 47-day certificates. Not fixing revocation, just making certificates expire fast enough that we can pretend revocation doesn’t matter.

The future isn’t better certificate revocation. It’s accepting that revocation failed and building systems that assume it doesn’t exist. That’s why we built CertKit. If we’re stuck renewing certificates every 47 days anyway, might as well automate it properly.

Because the one thing worse than broken certificate revocation is manually managing certificates that expire every month and a half.

CertKit automates certificate lifecycle management for the post-revocation world. Since we can’t revoke certificates, we might as well make sure they never expire.

Don’t misunderstand - I agree that revocation has problems. Not completely broken as you imply, though. CRLSets/CRLite, OneCRL, valid. Browsers/OS vendors require and ingest CRLs for revocation. They push revocations out-of-band, so of course browsers don’t directly pull CRLs anymore. Browsers haven’t ‘given up’, they just changed tactics. And yes, shorter cert lifetimes will help (not that the initiative was just to fix revocation, that’s a misconception).

If you truly believe it’s broken and doesn’t work - I invite you to revoke all the certificates on your website and servers/services, do that seconds after you request a new certificate. Then report back if revocation is indeed ‘broken’.

@Nick F It’s broken from a “does it work to reliably stop the certificate from being used” point of view, which many IT folks assume is true. This flaw has been acknowledged and discussed extensively in the CABForum message boards. Clearly, no one has abandoned it because of all these band-aid technologies to help solve emergencies, but that’s really what its good for: large scale emergencies.